Lancy Pont Rouge 46°11′9.402″N 6°7′29.809″E

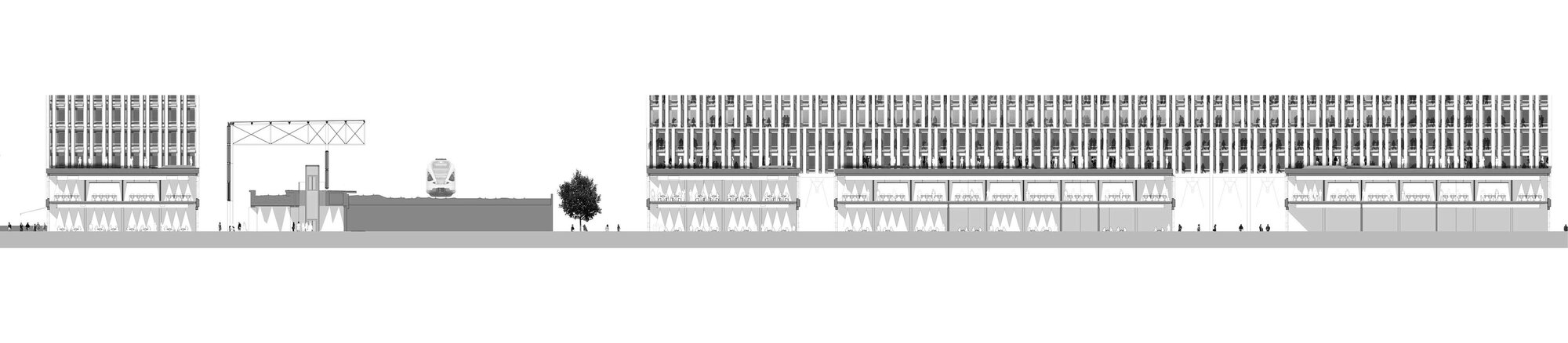

This passage increases the building's permeability and reinforces the open character of the development. In the same way that the SBB unified the country by adopting standard signage and a homogeneous architectural language, PONT12 grafts a typically Swiss generic language into this part of the city, which could be found in Zurich as well as Basel or Lausanne. The homogeneous ensemble is distinguished by a three-dimensional stone ribbon that runs through the site from east to west, and which functions sometimes as a bench, sometimes as a gutter for the flow of rainwater. This white ribbon, designed by the landscape architects of the Raderschall Partner firm, unifies the succession of small squares that make up the majority of the development.

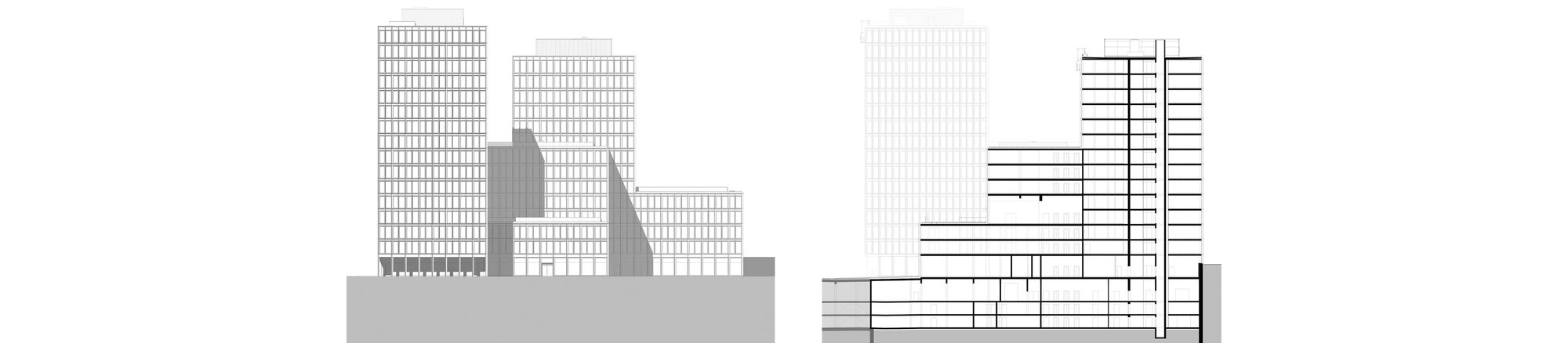

While all these elements converge and already allow us to broadly describe the future neighborhood, it is difficult to guess the final element that will be added in the coming decades: vegetation. The development has planned the planting of very large trees that could eventually reach the 58-meter height of the building. In addition to the species chosen for this purpose, wells cross the basements to seek the open ground beneath the last underground level. This costly device remains hidden from users today. Only the size of the trees between the buildings will one day demonstrate the State of Geneva's concern to allow the growth of very large trees on such a dense site.

Pont-Rouge therefore constitutes an ecosystem diametrically opposed to what pre-existed there, and to what persists on the other side of the Grand-Lancy road. This new district is the absolute antithesis of the free port, this mecca of hidden wealth. Instead of disruptive camouflage, Pont-Rouge advocates an open, porous architecture, conditioned for exchange and work. This conditioning does not prevent the new district from claiming a certain hedonism, notably in its way of arranging the components of the project, and of presenting itself as a portion of the hyper-center.